Reflections on the 13th Berlin Biennale

Mila Panić, Big Mouth (2025); Photos taken by Lihi Shmuel

There’s something about walking into a former courthouse, its walls soaked in institutional history, now filled with fragile voices of resistance and exile. The 13th Berlin Biennale, curated by Zasha Colah, unfolds across charged locations like this — Moabit’s criminal court, Sophiensæle, and other former halls of power — holding space for works by artists who live in displacement, silenced by regimes that still rule their homelands.

This edition leans heavily toward Southeast Asia, with a particularly sharp focus on Burma/Myanmar. Many of the artists are in exile. Some works are posthumous homages — to artists imprisoned, censored, disappeared, or dead. Against that backdrop, the 12th Biennale’s title, Still Present!, doesn’t feel like a statement — it feels like a dare. A demand. A whisper of defiance.

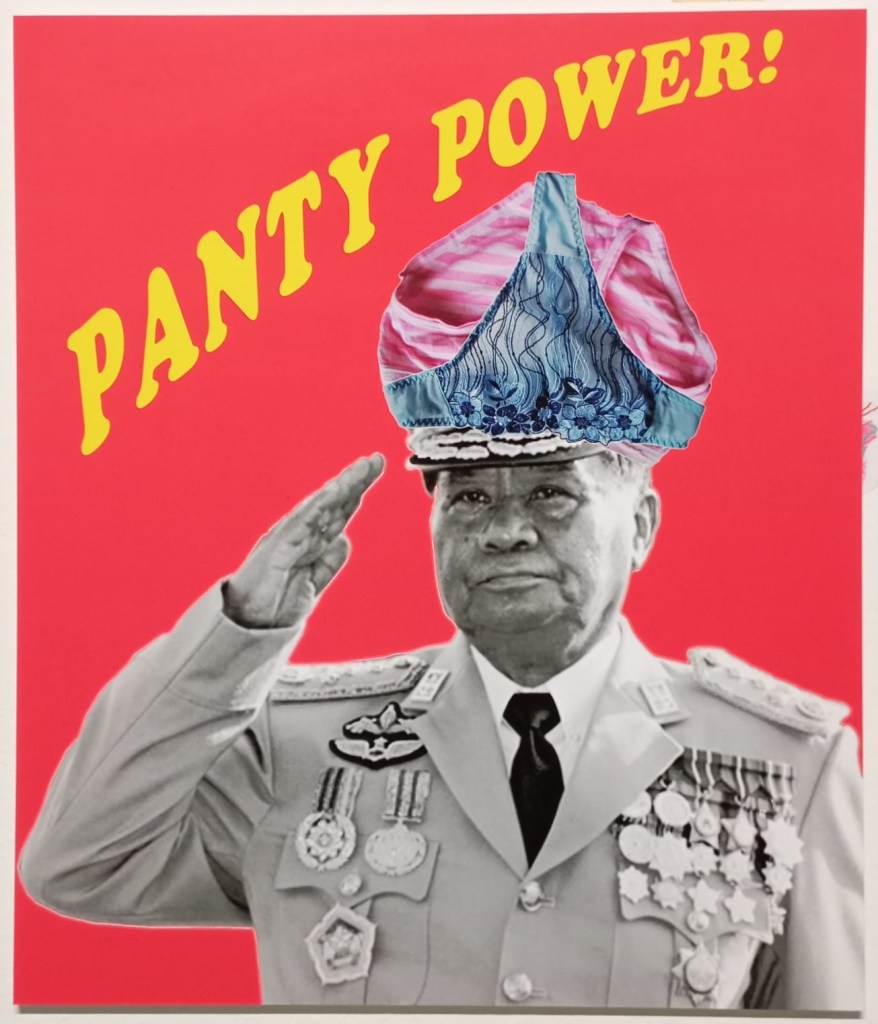

Two works stay with me. One is Panties for Peace, a reference to the protest campaign launched by Burmese women in exile in 2007. In response to the regime’s violent crackdown on the Saffron Revolution, these women called on supporters to send their used underwear to Burmese embassies. It was ridiculous and sharp at once — used panties mailed in protest, aimed right at a regime scared of women’s bodies. That’s what stuck with me. The softness wasn’t soft. It was charged. Funny, angry, intimate. A kind of protest that giggles while it cuts. The Biennale’s display doesn’t reconstruct the campaign in full, but its spirit hangs in the air — delicately sewn, suspended, and sharp-edged.

In the same room, puppets are scattered around, replicating scenes of protests. Chaw Ei Thein’s Artists’ Street uses hand-stitched textile sculptures to map decades of artistic resistance against Myanmar’s military regime, from the 1996 student demonstrations to the 2021 coup. Her work is more than a memorial — it is an act of embodied resistance. Through a feminist and grassroots lens, she weaves together personal memories and oral histories to trace not only a legacy of struggle but a blueprint for continued defiance.

This stitched-together street felt like a mourning ground and a kind of sketchbook for how we might keep going. Not a neat monument — more like a restless whisper that doesn’t stop moving. I was lucky: Chaw Ei Thein walked me through it herself. Without her presence — warm, attentive, generous — I wouldn’t have understood the emotional weight. Her guidance gave the piece a pulse. It transformed from poetic abstraction into a map of what can no longer be seen.

Panties for Peace, Panty Power Attack (2007); Photo taken by Lihi Shmuel

At Sophiensæle — once a political theater in Berlin-Mitte, now a site of experimental and postcolonial performance — I encountered Amol K. Patil’s work. His installation traces his father’s legacy as a Dalit poet and activist, blending movement, sound, and political refusal. But again, it was Amol’s own presence that translated the work’s urgency. He spoke of inherited struggle, encoded resistance, and the slipperiness of visibility. In that space — historically built for public voice — his whisper felt like the most coherent thing. These moments of direct translation, artist to visitor, felt essential. Without them, much of the exhibition risked dissolving into poetic noise.

But beyond these encounters, I struggled. So much of the Biennale speaks of jumping — literal and metaphorical. Jumping from buildings. Jumping across borders. Jumping into water, into freedom, into death. Birds appear again and again — winged metaphors for escape, exile, flight. It’s moving. It’s visually rich. But the texts are vague, the context thin. I kept asking: why now? why Myanmar? why Berlin? What are we meant to carry away from this curated grief? I wanted more anchoring, more clarity — something to hold onto in a flood of pain.

And maybe it’s just where I am right now. My family is in a warzone, and I can’t stop refreshing the news. I’m carrying one grief and stumbling into another. It’s too much. The art speaks of symptoms — suffering, censorship, longing — but rarely points to the root. It’s all aftermath. No fuse, just smoke.

Then I stumbled into a small booth, almost at the end of my visit. A phone booth capped with a Zambian thatched roof — part shrine, part satire. This was Doctor Bwanga, a fictional traditional healer constructed by Bwanga “Benny Blow” Kapumpa. The artist invites visitors to call the Doctor and receive algorithm-generated advice — a mix of ancestral soothsaying and AI absurdity. He asks: why do we easily trust digital myths, but doubt traditional knowledge systems? Why are we more willing to believe Siri than a healer?

I picked up the phone and asked: why is fugitivity coming up again and again, especially now, in such politically explosive times?

The voice replied with a metaphor:

“Every time society speaks of fugitivity, it comes from a movement — from running. But what are we running toward? And what are we running from? It’s like steam in a kettle. When the water boils, it whistles. But what is singing under the lid? Not the water, but the fire beneath.”

That line pierced something. So much of the art speaks to steam — grief, exile, escape — but not to the fire: the political conditions, the broken systems, the wars that cause it all to boil over. The show presents the effects of violence, but not always its structures. We hear the whistle, but the flame remains unnamed.

And that’s the problem. The Biennale gives us fugitivity as atmosphere — a haunting, a mourning, a beautiful fog. But fugitivity is not a theme. It is a symptom. The real questions lie underneath:

Who is running — and who is being hunted? What are they running from? Who benefits from their silence? Who keeps lighting the fire?

Until we start naming the fire, the steam will only rise.

Isaac Kalambata, Bamucapi / Witchfinders (2025) – A collage-based work confronting colonial legacies through the symbolism of witchcraft in Zambia; photo by Lihi Shmuel.

Leave a comment