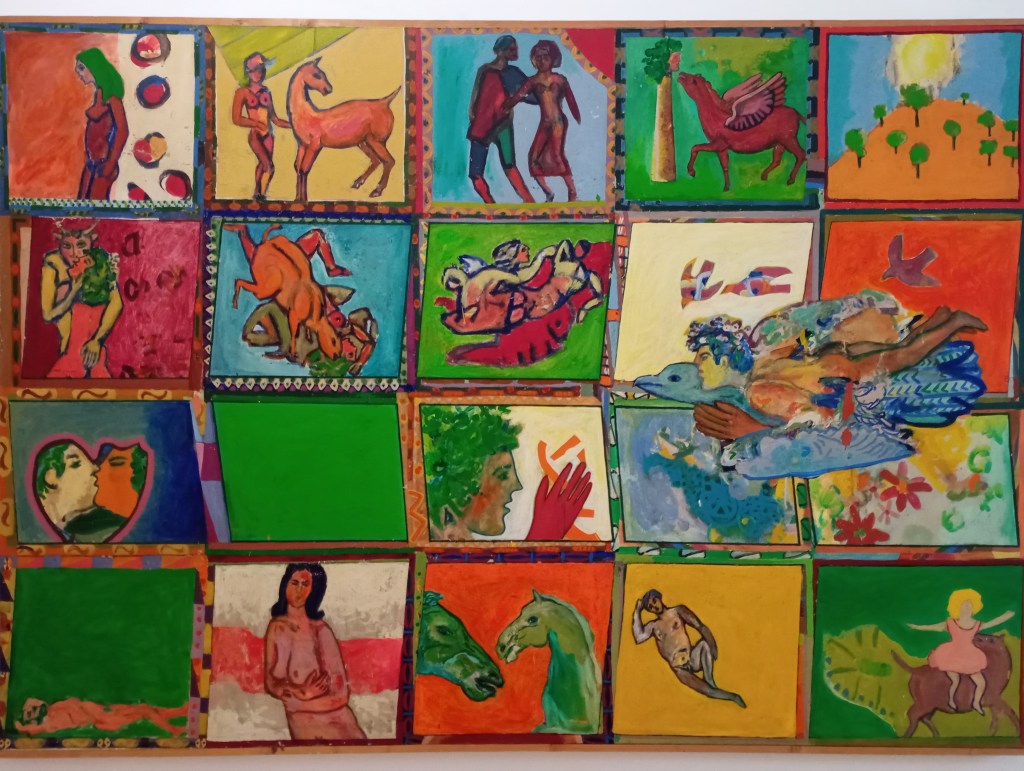

Paraskos Stass, “Pagan Spring” (1968)

Under the scorching Cypriot sun, I was thrilled to have an air-conditioned pause at the State Gallery of Contemporary Cypriot Art, located in the heart of Nicosia. With the island’s rich and layered heritage—shaped by its position at the crossroads of continents and influenced by Greek, Turkish, Middle Eastern, and British cultures, alongside its ancient past and its status as “the last divided capital in Europe”—I expected the gallery to reflect that complexity.

I did some research beforehand and received enthusiastic recommendations from a local guide, who expressed that Cyprus is actively working to develop its contemporary art scene. The country is gaining international visibility—largely due to tourism and real estate investments—and institutions are supposedly evolving to match. However, visiting was already a logistical challenge: the gallery is open only from 10:00 to 16:45. Founded in 1994 by the Department of Cultural Services, the institution was intended as a national space to institutionalize modern art and present Cypriot artistic identity on a permanent stage.

But I wouldn’t say it lives up to the promise. If I had matched with the gallery on a dating app, and arrived to meet her in person—I’d feel like I’d been catfished.

I’m not sure who curated the exhibition, but clearly “the more, the merrier” was their guiding strategy. Across all three floors, the walls are densely packed with paintings organized by artist, but with no visible curatorial thread. A few separate rooms attempt thematic categorization—Expressionism, Modernism, Cubism—offering a wide repertoire. Yet within these movements, the works feel disconnected, related only by superficial aesthetic traits. In some cases, the placement of the artwork was simply disrespectful, for example, on top of a power box, or in the corner under the stairs, hiding away from visitors.

The gallery is arranged chronologically: beginning with early 20th-century pioneers of Cypriot art like Telemanchos Kanthos and Adamantios Diamantis, progressing through mid-century works, and culminating in post-1974 pieces responding to displacement, division, and trauma. But even that trajectory is muffled by the erratic placement of the works, which distracts from the deeper messages embedded in the art.

On the left: Savvidou Koula, “Sleep-walker’s dream” (1990), “The recluses passage…” (1996). Unfortunately, there was no information on the sculpture on the right.

As I was the only visitor, I approached the kind woman who had opened the door and asked if she could tell me more about some of the works I was drawn to. With a warm smile and hesitant English, she admitted she didn’t know much about the collection but would search for a catalogue. After a few long minutes, she returned with one. We flipped through its pages together—each offering only three or four lines about the artists. I noticed the publication date: 1997. She confirmed it. That was the year the exhibition opened—and it has remained unchanged ever since. She didn’t see why I was so surprised. She moved on to the next catalogue, titled Young Cypriot Artists—from 1998. With all due respect, they’re probably not so young anymore.

Wandering through the gallery, I wasn’t exactly upset—just underwhelmed. Cyprus clearly has the potential for a vibrant, contemporary art scene, but what I saw felt stuck in the past. I expected more depth, more context, maybe even a bit of risk-taking. Instead, the experience left me with a sense that the official narrative was doing most of the talking.

You might ask: “Why didn’t you visit the new SPEL building in Nicosia? It launched in 2019 and hosts rotating exhibitions.” Well, they’re only open when exhibitions are on—which hasn’t been the case since March. “What about the Municipal Art Gallery in Limassol? You spent the weekend there.” Sure—but they’re closed Saturday and Sunday, and on weekdays only open from 07:45 to 14:45.

When I told this to local peers, they simply nodded. “It makes sense,” they said. Cyprus has a deeply rooted tradition of state-centered cultural policy. This influences how institutions are funded, curated, and preserved. Historically, state-run galleries have prioritized preservation over experimentation—promoting a unified national identity through art, often in response to the island’s division after 1974. Permanent exhibitions rarely rotate, functioning almost like shrines to a fixed narrative of ‘Cypriotness’—a cultural still life.

The nostalgia is palpable all across the island, but especially in Nicosia. Barrels and barbed wire still stand beside the old Paphos Gate. An abandoned UN base sits eerily in between. Weathered Turkish inscriptions remain etched above crumbling doorways. The streets speak clearly—and the state does its best to preserve that story. Meanwhile, tall hotels rise in the distance, parks are paved for tourists, and a quiet duality settles in. Things move slowly. They happen in their own time—unless someone from abroad comes ready to pay. “Come back to invest!” said the tour guide during our city walk—as did nearly every English-language billboard.

So yes, it all makes sense. The feeling that the State Gallery is “stuck” in the past is not an accident, but a mirror of Cyprus itself: a place where tradition outweighs innovation, and slowness is part of the rhythm. A country where the official narrative is preserved, not challenged. Still, I hope that amid its growing expat community and a rising generation born into a divided land, institutions will begin to reflect a more complex, contemporary Cyprus. One that gives voice to the artists working to tell the island’s present—and future. Or at the very least, opens its doors on weekends.

Leave a comment