Reflections on LCCA’s (Latvian Center for Contemporary Arts) Summer School under the title “Art, Agency and Institutional Transformation“

Photo by Paula Zariņa Šteinerte

I arrived in Alūksne with too many questions and not enough answers. By the end of the Summer School, I had even more. But perhaps that was the point — not to arrive at clarity, but to learn how to hold contradictions without trying to resolve them.

The program itself was centered on questions of institutions, critique, access, and labor — how they shape the art world, and how we as participants might challenge or reimagine them. These themes carried through every lecture, discussion, and exercise, becoming threads that wove together our reflections in Alūksne.

The town itself set the tone. Small, quiet, with a lake reflecting pale skies and forests leaning in from every side, Alūksne seemed to watch us as we arrived. It was the kind of place where the air feels slower, where conversations can stretch out over coffee or along empty streets, and where small observations suddenly carry weight. In that calm, our questions about institutions, critique, and access felt sharper — and also more fragile.

Institutions in Conversation

From the start, institutions hovered over every conversation. What does it mean when one institution invites another to collaborate? Almost always, the invitation takes a familiar form: an exhibition, a panel, a residency. The exhibition has become the default medium of communication in the art world, so dominant that it risks suffocating other possibilities. That question returned: what other forms of collaboration could exist if we dared to move beyond the white cube?

It quickly became clear that institutions exist in tension with themselves and with others. Anti-institutions, which position themselves as alternatives, often end up reproducing the very logics they resist. Their critiques are absorbed, formalized, and mirrored back. Institutions and their critics feed off one another until the line between them blurs. Broad statements about “the institution” risk flattening complexity, reducing people, negotiations, and history to a caricature.

Archiving and Nuance

Our conversations led us naturally to the idea of archiving, particularly through discussions led by Marika Agu and Sten Ojavee on Archie and Soros Realism Revisited. At first, it seemed like a technical topic, almost bureaucratic. But in practice, it became something much more subtle: a way to protect nuance, context, and meaning. Without attention to detail, gestures, statements, or actions can be lifted from their original context and misused. The archive is not just a storage of works; it is a record of relationships, debates, and contradictions — a way to hold complexity rather than simplify it.

Humor and Critique

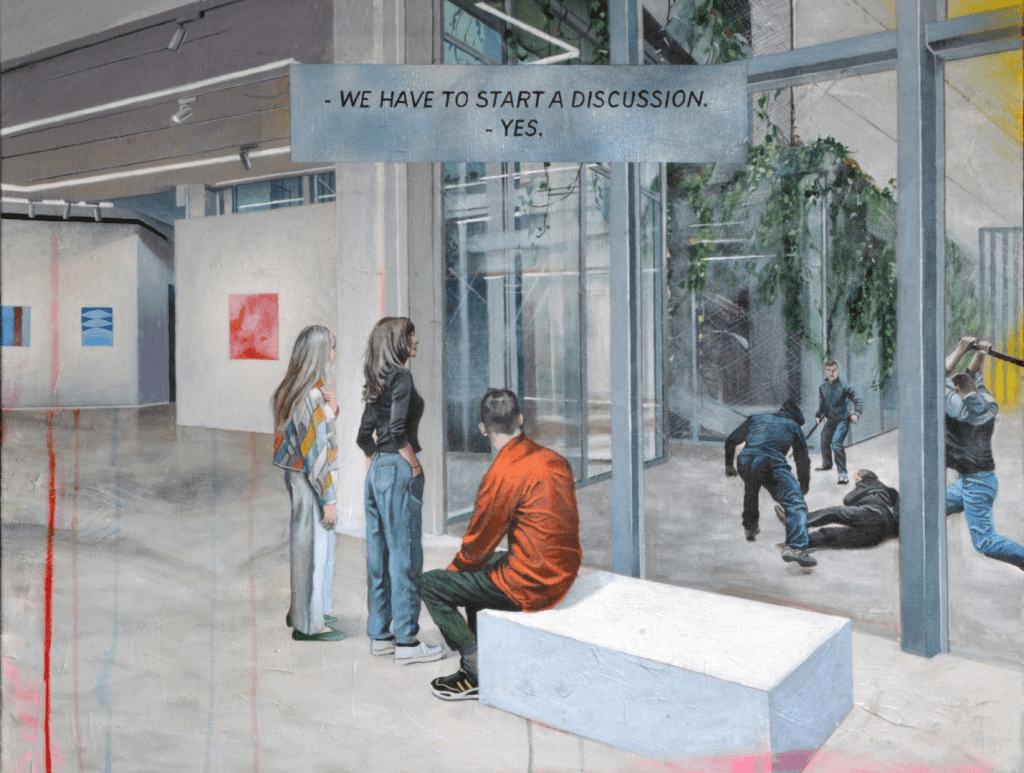

“Walled In” (2025) by Alexei Gordin

While archiving preserves subtlety and complexity, other forms of reflection — humor, absurdity, dialogue — reveal the human contradictions that archives cannot capture. Even in the midst of these heavy ideas, humor emerged as its own form of reflection. During his talk Alexei Gordin’s said: “People gather in the safe space of galleries to speak about how unsafe the world is.” There is something absurd — almost cruel — in that phrasing, yet it felt perfectly true. It captures the strange duality of art spaces: they offer safety, comfort, and containment, yet simultaneously remind us of the fragility, tension, and instability of the world outside. The humor lies in that tension, in the way a supposedly “safe” environment can become a mirror for all the uncertainties we carry. And it made us laugh — not just at the absurdity, but at the recognition of our own contradictions within these spaces.

Critique itself, as discussed in depth by Santa Hirsa, functions not simply as analysis or judgment, but as a relational, participatory act. It is something that happens between people: in conversations, in debates, in shared observations. Humor becomes a key tool in this process. It allows critique to be incisive without being alienating, to highlight inconsistencies and absurdities in institutions, artworks, or systems, while keeping the dialogue open and human.

During the Summer School, I noticed moments when laughter emerged almost spontaneously — a commentary on the hierarchy of the art world, a joke about the rituals of exhibitions, or a playful questioning of the assumptions we brought with us. These moments revealed contradictions that might have been invisible in serious discussion. Humor, I realized, can be as sharp as theory: it disarms, it connects, it makes critique feel alive rather than distant. In this way, lightness and reflection exist side by side, showing that critique need not always be solemn to be meaningful. These playful, human moments intersect with questions of access and labor, showing that critique and participation are lived experiences, not abstract concepts.

Accessibility, Language, and Labor

Questions of access and language were never far away. Who gets to critique? Do visitors feel allowed to, or are they simply recipients of authority? Language sets the tone: simplified language is not a simplified story. It is an opening, a way for people to enter the conversation without being excluded. Critique becomes meaningful only when it is not confined to the already-initiated — when it reaches those outside institutional walls, who experience art differently, or who bring fresh perspectives we might not expect.

Labor, too, was unavoidable, particularly in the lecture by Yana Foque. Cultural work is work, yet it is rarely recognized as such. We often celebrate the idea of the “artist who survives solely on their practice,” treating any side job as a failure or compromise. But Yana highlighted that this myth overlooks the complexity of sustaining a creative life. Many artists navigate multiple forms of labor — teaching, assisting, curating, writing — not as a fallback, but as part of their practice. These parallel forms of work can provide stability, open new perspectives, and allow artists to experiment without the pressure of the market dictating every move.

In this sense, labor is inseparable from artistic practice. It shapes rhythms, priorities, and interactions, and it can even inform the work itself. Understanding this makes it easier to see precarity not as a personal failing, but as a structural condition that requires strategy, resilience, and care. Recognizing labor as part of art practice also opens a conversation about value: whose work gets attention, whose is overlooked, and why. Survival, then, becomes part of the creative act itself — not a distraction from it, but a lens through which art, critique, and society are understood together.

At Least It’s Better than Crime: Creative Project

The artistic project in Alūksne brought all of these questions into focus. As part of the curriculum, we were divided into groups, each tasked with producing a response — an “Artistic Project” that reflected on the themes raised in the seminars. Together with Kristofers Kārkliņš, Paula Stutiņa, and Smaranda Krings, and influenced by Alexei Gordin’s practice and lecture, we created a conceptual short film exploring not only how the citizens of Alūksne perceive artists, but also how our presence there as a temporary institution shaped those encounters.

This became, in essence, a form of institutional critique. By asking locals what an artist is, we weren’t only gathering definitions — we were also holding up a mirror to our own role as participants of the LCCA Summer School. We were outsiders, arriving with the authority of an institution, requesting answers from a community that hadn’t invited us. The responses revealed as much about that dynamic as they did about art itself.

More than half of the people we approached didn’t want to answer at all — a refusal that itself can be read as a commentary on the limits of institutional outreach. Among those who did respond, answers ranged from casual to profound: “an artist is someone with a side job,” “someone who makes dreams come to life,” and, most memorably, “we are all artists.”

Through these fragments, it became clear that art occupies multiple positions within society: distant, central, irrelevant, essential. Some locals were indifferent; some were deeply reflective. We attempted to create a bridge between our temporary institution and the local context, observing how curiosity, skepticism, and misunderstanding coexist. In that sense, the project was less about defining the role of the artist, and more about questioning the structures through which institutions enter communities and frame those conversations.

Ultimately, what Alūksne offered was not resolution, but perspective. The Summer School reminded me that art, critique, and institutional work are never isolated. They are woven into networks of labor, participation, humor, and society. The questions remain open, but in that openness lies their strength. Observing, listening, engaging, and reflecting are themselves forms of practice, as vital as any exhibition or written analysis.

Perhaps the true value of these experiences is not in finding answers, but in cultivating the ability to notice, to connect, and to hold dialogue — between institutions, artists, audiences, and society at large. In this way, art becomes a space where complexity is not solved, but lived, shared, and explored.

Leave a comment